I have dreamed of the green night of the dazzled snows,

The kiss rising slowly to the eyes of the seas,

The circulation of undreamed-of saps,

And the yellow-blue awakening of singing phosphorus!

RIMBAUD

A Dark Star

Harar is undoubtedly Ethiopia’s brightest flower. As a jewel, she may be slightly chipped around the edges, though her centre continues to shine with undiminished brilliance. Of course, like most places on the African continent - which Paul Theroux encapsulates as ‘a Dark Star’ - everything in this town located on the border of the far eastern Somali region is a bit messed up.

French-imported blue and white vintage Peugeot taxis cruise beneath Italian-built colonial buildings decked with tropical flowers, giving a strange Cuban twist to Sunni Islam’s fourth most holy city after Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem.

The narrow winding streets within the perimeter walls are alternatively whitewashed then painted in pastel shades of blue, viridian, vermillion. While the bitter smell of marijuana smoke is the lifeblood within the fortified walls of Morocco’s northern Blue City of Chefchaouen, here it is khat, the highly addictive leaf grown on the surrounding plains, releasing an amphetamine buzz when chewed, and occupying the daily thoughts and actions of the majority of the city’s inhabitants.

Men dye their beards orange. Women wear the most ostentatious, beautifully designed and brightly coloured shammasin the whole country. There are tramps everywhere.

A little history and spice

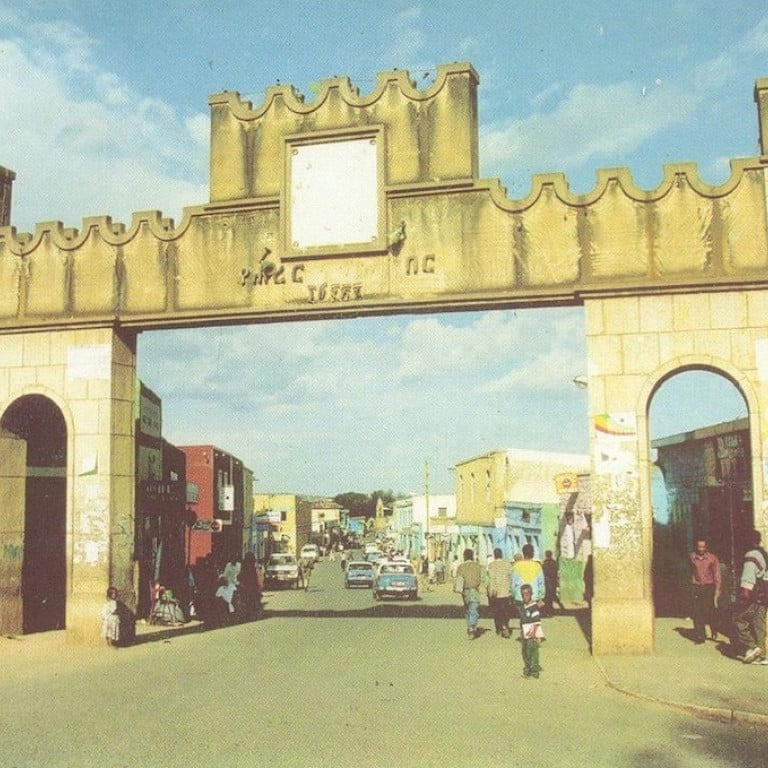

Founded by Sheikh Aw Abadir in 940 A.D., the Harar Kingdom built 99 mosques according to the 99 names of God referred to in the Quran, of which 82 remain today. The four-meter-high limestone wall - or Jugol -encircling the old city was constructed from 1551 to keep invaders at bay, although it has often not been successful.

The city has been conquered over the centuries by numerous kingdoms including the Adal Sultanate, the Egyptian Caliphate, the Oromo tribe (who advanced through the Rift Valley from the southwest on horseback, sacking the city before converting to Islam), Abyssinia (under Menelik II), and the Italians. Harar has historically been one of the main trading hubs between Africa and Arabia, dealing in slaves, principally from the Oromo region (Muhammad’s wet-nurse is said to have been Ethiopian), hides, coffee, khat, ivory, gold, perfumes, incense, musk and salt.

Harar’s walls were not penetrated by the Western World until 1855 when British explorer and poet Sir Richard Burton, disguised as a Muslim, entered through the northern gate and stayed for ten days after secretly visiting the holy city of Mecca a year earlier.

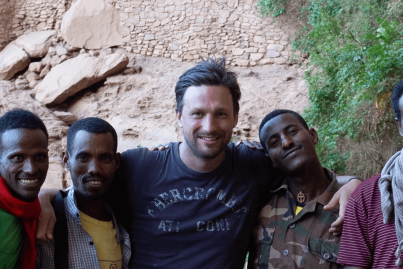

I met my guide, Girma, at 8.30am after he had industriously knocked on my door an hour after my arrival the previous evening to offer his services. An ex-radio operator for the Air Force - (“I have jumped from a plane!”, he told me) - he served as a young man in one of the many wars with Eritrea and in Somalia.

After a delicious breakfast of pancake covered in a thin omelet dipping in honey, we set out to explore to the city. We entered the walls through the southeastern gate - there are five gates corresponding to the five pillars of Islam - and immediately found ourselves in the spice market. The floor was covered with many discarded khat leaves. Chatter filled the air in Ge’Sinan or ‘Harari’, a mix of Amharic, Arabic, Afaan Oromo and Somali only spoken within the city walls.

Sheltered by orange tarpaulin, large calico sacks overflowed with anise, cardamom, coriander, dill, mustard, chick peas, lentils, various types of incense, basil, garlic, khat, rosemary, oil beans, yellow coffee, frenjer (no idea), abish (a spice drunk by women after pregnancy), piles of sugar cane and a whole host of other colourful and exotic paraphernalia.

Haile Selassie's coronation

We continued through winding streets until we reached the governor’s house. Ras Tafari, later known as Haile Selassie, was governor of the city in his youth and his old house is now home to an excellent museum. As Ethiopia’s last emperor, he renamed the country from ‘Abyssinia’ in 1963, and is worshipped as a god incarnate among the followers of the Rastafari movement. The name is taken from his pre-imperial name: Tafari Makonnen, with Ras - meaning ‘Head’, a title equivalent to Duke.

The Rastafari religion emerged in Jamaica during the 1930s under the influence of the Pan Africanism movement, with Selassie viewed as the messiah who would lead the peoples of Africa and the African diaspora to freedom. With his Solomonic lineage and official titles of Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah and King of Kings and Elect of God, he is perceived by the Rastafari as the returned messiah as prophesised in the Book of Revelation in the New Testament: King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, and Root of David.

Haile Selassie visited Jamaica on the 21st April 1966 with approximately 100,000 Rastafari from all over the country descending upon the airport in Kingston in a haze of ganja smoke to greet their messiah. This date is still commemorated by the Rastafari as Grounation Day, the anniversary of which is celebrated as the second holiest holiday after the 2nd November, the emperor's Coronation Day.

The coronation of Haile Selassie in November of 1930 was a pivotal event that catapulted the relative backwater of Abyssinia to the forefront of world’s attention. British writer Evelyn Waugh’s personal account of the event perfectly conveys the uncertain magic and botched brilliance of the country, with the following passages taken from Remote People, published in 1931.

“At long intervals the emperor was presented with a robe, orb, spurs, spear, and finally with the crown. A salute of guns was fired, and the crowds outside, scattered all over the surrounding waste spaces, began to cheer, the imperial horses reared up, plunged on top of each other, kicked the gilding off the front of the coach, and broke their traces. The coachman sprang from the box and whipped them from a safe distance…

“It was now about eleven o’clock, the time at which the emperor was due to leave the pavilion. Punctually, to plan, three Abyssinian airplanes rose to greet him. They circled round and round over the tent, eagerly demonstrating their newly acquired art by swooping and curvetting within a few feet of the canvas roof. The noise was appalling; the local chiefs stirred in their sleep and rolled on to their faces; only by the opening and closing of their lips and the turning of their music could we discern that the Coptic deacons were still singing…”

Arthur Rimbaud

We stopped off at one of the blacksmiths’ yards where sweating men sat around a furnace powered by an electric fan that whipped up the fire in a kiln to a blistering degree. The men chewed khat and used hammers to bang away at plow-tips and axe-heads. Ash from the fire filled the compound. It was like walking into the Middle Ages.

Outside, women paraded the streets in shammas of every possible combination of pattern and colour you can imagine. By tradition, only unmarried girls are supposed to wear full silk dresses; married women distinguishable by only the upper parts of their dresses being in silk, the lower in cotton. From what I saw, however, I’m pretty sure that this custom has been metaphorically ‘thrown to the wind’ with some very married-looking women wearing some very beautiful all-silk-looking dresses.

The acclaimed French poet Arthur Rimbaud arrived in Harar 25 years after Burton in 1880, and, having renounced his huge successes as a poet, lived there for between ten and eleven years as the first white trader of coffee and arms in the city, although he never seemed make much money.

I had been lucky enough to find a copy of his works in Addis and for a time became engrossed in his tumultuous life story: his lover Verlaine shooting him in the wrist whilst drunk; his feats of genuine exploration in the region; his heart-breaking final letters home as he was carried across the desert in immense pain with a cancerous knee, later amputated, causing his death shortly afterwards in Europe. And, of course, his mystifying poetry interwoven with alchemistic incantations, threads of the occult, colour, light, and magic. Harar was just the place for a man like him.

Rimbaud imported the first camera into the city and on the second floor many of his fascinating prints are on display. I spent a long time looking at them before returning to my room in one of the traditional guesthouses within the jugol. All Harari houses are of a similar layout with a large multi-platformed seating area, its levels of seating according to social rank.

Colourful plates and wickerwork fill every inch of the whitewashed walls. Wooden beams protrude in a line across the entranceway, the number of rolled-up rugs placed over them indicating how many girls are of marriageable age in the household. Girma and I rested at one of these, while the girl of the house prepared coffee for us.

The Ethiopian coffee ceremony

Harar coffee is considered to be one of the best coffees in the world. Spicy, full-bodied with an almost wine-like texture and taste, Harar beans are some of the oldest still in production. The coffee is naturally sun-dried, the sugars of its red fruit caramelizing and imparting its flavours into the bean itself - a crucial aspect of the overall taste.

Ethiopia is the origin of all coffee. A famous story originates from the village of ‘Buna’, now the Amharic word for ‘coffee’, in the ‘Kaffa’ Biosphere Reserve (which is where the internationally recognized word for ‘coffee’ originates) in the lush jungles of the southwesterly collection of tribes called the Southern Nations. Many moons ago, a goat herder in the forest saw his flock acting strangely after having eaten some red berries from a bush he had never seen before.

He collected some of the mysterious berries and took them home to his wife, who cooked them using the wood fire in the centre of their thatched hut. She discovered that if the beans (two half-spheres separated by a membrane inside every berry) were first roasted over a flame and then ground down into powder, they would release their magical properties.

Coffee has since spread to be the national drink across the entire country, and is accompanied by the ancient Ethiopian coffee ceremony. Fresh green grass leaves are strewn across the floor while a woman - nearly always wrapped in the traditional light shawl called netela - goes through the rather long process of roasting, grinding and brewing the fresh coffee over a fire.

She wafts the smoke from the roasting beans over the brows of her guests, who sit around her on wooden stools, as a blessing. The buna is brewed in a large black rounded clay pot called a jabanah before being poured into very tiny white porcelain handleless cups, mixed with a veritable mountain of sugar. It is rare for a guest to have less than three cups at a single sitting. Their cup is always dipped in a pail of water before each refill.

The coffee ceremony is the central point for so much of Ethiopian community life and, as Sheik Abd-al-Kadir commented in 1587, "coffee is the common man's gold and like gold it brings to a person the feeling of luxury and nobility".

Hyena madness

In the evening Girma and I caught a bajaj to the outskirts of the wider city to the rubbish dump at twilight. Here the local hyenas are fed daily and my eyes fixed on them intensely as they emerged from the shadows of plastic-strewn wasteland. They are huge, much larger than a dog, and clearly built of solid, solid muscle.

Their long necks protruded forward large grizzled heads, seemingly eaten away in patches around the gums and lips either by dark markings or some terrible disease. I couldn’t tell which. Their slow lolloping gait betrays a terrible flashing rapidity of movement. Whoever said that they laugh was lying.

I fed them strips of raw meat draped over sticks along with a few other tourists. I was hazy on the ethics of feeding these wild animals, but truth be told I wanted to see them up close so I went along with it, although I have to say that once was enough. I found them truly frightening.

I thought back to my flippancy as I sat alone, high up in the mountains of Lake Hashinge in ‘the floating world’ on my previous hike; I had heard the caterwauling of a pack within a couple of hundred metres of me. Although human attacks by hyenas are not common, ignorance can truly be bliss sometimes.

Towards evening the pace of the city slows to a crawl as most of the men and many women start to really get into their khat highs and even the pretense of work is abandoned. Addiction to the drug has caused lots of old men to completely let themselves go, and it’s common to find them lumped in filthy alleyways with beads of green saliva spilling down from their mouths.

The really old men with no teeth grind the leaves in a mortar and swallow them as a paste. Some of them go crazy eventually. One youngish man had his feet manacled in the street outside his home. Bunches of khat leaves in his left hand, he grabbed my hand with his right and wouldn’t let go. He spoke good English and seemed well educated, but was clearly out of his mind.

Some of the men are revered for their holiness and Girma was very careful to pick out one man for me to give ten Birr to as an ‘offering’, although to me it just seemed a money-spinner for more khat. A gibbous moon drifted over the city at night to the wails of the muezzins from the mosques. Harar. Crazytown.