One thousand years ago, as King Lalibela lay in a poison-induced coma at the hand of his brother, he journeyed to Heaven where the angels commanded that he build a New Jerusalem in Africa’s then bulwark of Christianity. His stonemasons cut directly down into the living rock of mountainsides to achieve this, the church roofs therefore remaining at ground level. Standing in the dimly lit caverns with your hand pressed against the cold, rough surface of a pillar, you can feel that you are touching, and indeed inside yourself, a part of the natural world where men and women aren’t really supposed to be. The churches are not as finely carved as the cathedrals of Europe, nor do they hold the eye like the lines of the architects of Greece, and yet, sitting alone in the presence of these monoliths, I felt the force of time creep upon me quietly, like a whisper, as confusing as an un-remembered memory or the brief grasp of a language we do not understand, or old blood stirring; an index finger of knowledge touching the surface of a silvery pool. All at once it was whisked away and forgotten, and I was left blinking in the bright light of day.

Walking between the huge meter-thick pillars of Biete Medhane Alem, the air cool and clammy, there was a sudden power cut and I was left alone with two priests reclining on the floor by the parapet and a man praying in one of the corners of the giant edifice. There emanated from the very walls an atmosphere of peace and indeed, holiness. Speaking to a friend of a friend, an Ethiopian called Sammie on the balcony of the Sheraton in Addis months later, I relayed this experience to him: “Ah yes,” he had replied, “you can actually feel it.” The sanctuaries containing the Holy of Holies are covered from sight by huge curtains hanging on weak aluminum poles. These rest upon the brutish stone abaci of the supporting pillars. The cheap nylon of the curtains is patterned in gaudy, shiny spots or a 1970s rose-print, their shoddiness somehow endearing, being of so little importance within the grandeur of the setting. There is a general ramshackle feeling to the place. Huge rugs ten meters wide have been rolled up and left outside in hollowed-out grottos.

A tour around Lalibela ‘s rock churches

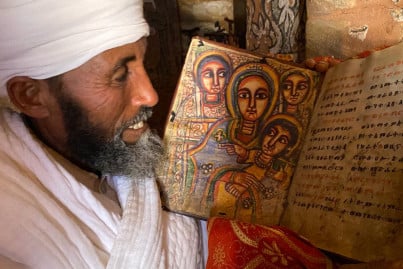

Men and women in cream robes sat around in circles on the floor eating, their cleft prayer sticks lying around at all angles. Power cables hung through the carved windows of an ancient swastika. An 800 year-old olive wood chest has its missing front section replaced with plywood. The worn floors are covered with cheap carpets, thin neon-tubed lighting making the smooth sections of the walls ripple like mercury. Candles flicker. Some of the ceilings are painted in tribal patterns and someone somewhere was beating a drum. The middle of three deep-set windows has a cross cut out of the wall above it, the window to the right of this a cut out rounded arrow pointing to heaven, the one on the left a cut out of a clunky arrow pointing down to hell: a representation of Golgotha where the penitent thief, Saint Dismas, is accepted into heaven. Subterranean tunnels lead you to the eleven churches past endless caves of odd sizes and indefinable purpose. A priest, sporting a white turban and rolled-up umbrella, emerged to open a locked door and let us inside Biete Amanuel, the private chapel of the royal family.

It is the finest example of the perfectly symmetrical Aksumite design. The sculptors have carved the stone to represent wooden beams that run along the walls on the inside, culminating in cubic ends that parade in a line below a vaulted, cracked ceiling. Sacred bees buzzed in their hive high up behind a small wooden door in the vertical walls of the rock courtyard. Biete Abba Libanos is hewn directly out from the strata of a cliff side, red carpeting and benches laid around its cavernous perimeter. At the corners of its doors and windows, huge cubes of stone jut out intimidatingly. Large hide drums lay on the floor. An ornately carved table was stored upside-down in a small cave halfway up the wall. A light bulb hung from a thin cable emitting a soft radiance. In the art of the frescos and the wooden framed icons, the latter propped up against walls or left lying around in strange places, all of the faces are Ethiopian. They are painted in bright colours in the way that Mexicans sometimes paint; shapes and bodies occasionally merging into each other for no reason, or if they don’t, they just have an unreal quality about them.

Ethiopian paintings and frescos in Lalibela

There are things in the paintings that you don’t expect to be there. When Saint George kills the dragon there is a woman tied to a tree. Under a depiction of the Virgin Mary holding a little Ethiopian Jesus the devil is painted with horns, claws and wings over flames; bright red manacles around his wrists. The four apostles look like Persian kings. It is raining when Jesus is crucified. Saint Merkorious is depicted killing Eulianos with a spear, his intestines spilling onto the ground while the Angel Gabriel looks on in a floating bathtub of cloud. Soldiers with dog heads carry spears. God himself, Abou, is a wise old man with a beard flowing down to his sandals and a cloak of feathers. He is flanked by docile lions and leopards.

My first impressions of Addis Ababa

In Addis Ababa a woman laborer shoveled cement on the third floor of the concrete mesh of a six-story building, one of the huge number of edifices in various states of incompletion that break through the undulating waves of roof tin that lap around a few modern hotels and skyscrapers on their way to the shores of the foothills in the distance. The corrugated metal sheet fencing around the construction sites are painted in alternating green and yellow, a purple blossom falls on the road between busy lanes of traffic. At the UN building the security bollards were being painted in a new blue. The thick latticework of an ancient acacia tree shaded embassy guards in aquamarine camouflage, lazy AK47s drooping over their shoulders. I glided above it all on the Chinese-built tram system, listening to the company’s marketing video in English as rusty rivers filled with trash trickled below and car fumes filled the altitude-thin air with haze.

I landed in Addis after transferring in Nairobi where I had chatted to a Kenyan family also heading to the capital. The view from the connecting flight was rather overpowering to my sleep-deprived brain, daunting even, in its magnitude of scope. Verdant plains and huge lakes soon gave way to the rising plateaux of Ethiopia, checkered fields, villages and broccoli trees crawling up the cliffs onto the tabletop steppes, through which mountains tore away, driving up shrub and stone. It was all so vast. I had the peculiar sensation of feeling that this was an unconquerable land, which I suppose it is. I was staying in Addis with some acquaintances that lived in a comfortable compound in the richest part of the city. This convenience emerged as a double-edged sword however as they had been living in Ethiopia for more than three years and were impatiently looking forward to returning home in the coming weeks; as a result I was only initially peppered with the negative aspects of the culture, making my first impressions rather glum indeed.

Other travels in Ethiopia

Thankfully after a few nights out and having wandered around the city a little, my outlook brightened considerably, with both Erica and her husband Sarunas charming and attentive hosts. After attending an embassy bazaar in the convention center and doing the usual round of bars and restaurants, Erica offered to show me the two towns she had lived in and was returning to for a final farewell. I did not actually like the towns very much but the journeys between both were mesmerizing. The roadside truck stop nowhere town of Debresina [translation: Debra–Mount, Sina–Sinai] sits at 3200m in the lap of a small mountain. Erica greeted old friends and we sat in a roadside coffeehouse comprised of a tin roof with curtain sides and cut grass strewn on the floor. The coffee or buna is as delicious as the guidebooks will tell you and we had several sugary cups perched on low stools while a group of local men sat around chewing khat leaves at the next table, its amphetamine-like properties giving a glossy shine to their eyes and a general air of indolence. Debrabirhan didn’t fare much better albeit with one exception.

Erica guided us to the famous arake bar on the outskirts of the larger town, down a cobbled street that smelled of shit leading to a vista that, in the fading light, resembled an Italian landscape from a Merchant Ivory film. We walked into a very large room with an earthen floor, wooden benches and tables skirting the walls. Many poor looking Ethiopians with sun-blackened faces – giving credence to the Greek origin of their name of ‘burnt skin’ – sat around these draped in white cotton shammas. Small shot glasses in front of them spilled a light amber liquid onto the dark wood. Children ran about, two of them hiding behind an embroidered curtain. The arake is distilled there from god-knows-what and can reach up to 80% proof. I found this hard to believe until I tried some. A shot is three Birr (it used to be two Birr), which is roughly six Cents US or four Pence Sterling. When you have finished one you either bang it down on the table indicating you want a refill or turn it upside-down. I banged mine down so hard the first time the whole place looked around and laughed. More of Erica’s local friends joined us.

Drinking in a local arak house with Ethiopians

One little girl insisted on kissing us on the cheeks. I began playing with the children behind the curtain and they giggled as I tickled them. They were a brother and sister named ‘Kidus’ and ‘Eyrus’ which translate to ‘Saint’ and ‘Jerusalem’ respectively. Mezemir Girma, who teaches at the local university, quoted Shakespeare to me and expounded on the five Sources of Knowledge, being, in an order the significance of which I didn’t fully grasp: Experience, Authority, Logic, Religion and Scientific Inquiry. One of his previous students, Genet, an attractive girl of 23 in a bob and tight fitting dress, sat next to me and was a delightful mixture of extreme religious piety and flirtation. A surly manager at the commercial bank who looked like a wrestler completed our party. The walls were covered with images of Jesus and Mary with one huge mural of the carrying of the cross.

This was complimented by an eclectic collection of paintings from an abstract artist who could have been commissioned by the War Office in 1945, with images of a man leaning on a stick, the rock-hewn church at Lalibela, a fox, a leopard, a zebra. A large photo of a girl holding a dove hung in the corner with a number of photos by a doorway of the landlady who had passed away two months previously. “Oh, I wondered why I hadn’t seen her.” She had been married to an officer during “the Imperial Time” (pre-1974). We moved on to a tedj house with orange walls, drinking the honey-fermented beer from glass potion bottles and clapping to a local man dancing, before going to a restaurant. We whizzed back to the capital on a good road through plains and terraced mountainsides of pastoral harvest scenery. Fields were flecked as far as the eye could see with pale fluffy-domed stacks of teff, having been reaped by hand then threshed by livestock to release the grass’ fine grain, used to make the injera flatbread served with every meal.

Describing the Ethiopian way of life in the countryside

The teff is piled into a huge fort with cattle, horses or donkeys driven around in a circle on the inside, pulling the walls down as they go to thresh the grass. Men, women and children, draped in shammas of simple design, squat in the fields using hand sickles of a dull metal, carefully laying the grass in neat piles behind them, all facing the same way. Fields of sorghum swayed in the sunlight. The farmers are highly industrious and every visible square meter of arable land was cultivated. The grass houses (sarbait) are round with dried dung walls or rectangular, the latter a small longhouse with two tied and folded summits of grass rather than one. Circular stonewalls link the houses and a few trees creating tiny hamlet compounds, which cannot have changed in design for millennia. Tin has been introduced and is used for many roofs (korkorobait) which although more practical, is not as romantic in appearance. Yellow and brown fields led down in scorched ripples towards rock-strewn rivers where children were herding goats with thin poles.

Circular, brightly painted churches at first glace appeared like Asian temples nestled in the eucalyptus groves. Eucalyptus is unfortunately the dominant species in the country after having been introduced by Menelik II for construction of the then new capital. It has since spread across the country like wildfire and consumes a huge amount of the soil’s moisture, its acidic leaves also having a harmful effect. They are undoubtedly pleasing in appearance however, with the younger shoots rising up from a soft turquoise to a pale pink, releasing their delicate fragrance into the breeze. Lone acacias shelter animals on the hot plains or group together in groves on hillsides. The mountains rose up in a tortured splendour with ferocious chasms leading off into the distance, exaggerated like the backgrounds of religious paintings. One particularly enormous gorge cleft the entire landscape in two in the hinterland as if God Himself had drawn his sword across the country. It is a biblical landscape. Four women wrapped in dark shammas walked in single file to the river balancing wicker baskets on their heads, children played at hitting each other with long poles, the men bathed unashamedly naked.