In the middle of the 4th Century AD, Saint Frumentius brought Christianity to the Axumite Kingdom in what is now northern Ethiopia. A Syro-Phenician Greek, he was captured with his brother as a boy, becoming a slave to the King of Axum. Upon obtaining their freedom, the brothers educated the King’s heir in the teachings of Christianity, and Frumentius was later appointed as the first Bishop in Axum by the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, whose Pope then also oversaw the Christians of Syria. According to local tradition the churches in the Gheralta Mountains were constructed in the 4th Century by the first Christian kings of Ethiopia, Abraha and Atsbeha, although it is more likely that many are 6th Century constructions, from the time when monasticism was spreading throughout the region. Many of the hermitage caves were expanded to become the enormous edifices that can now be admired flickering in candlelight amid the murmurs of the cream-shawled faithful. The churches have been hewn directly out of the mountainsides by hand, only their slim rock pillars left in place to prevent collapse.

The churches in the Gheralta Mountains

They are found in high, remote places to fend off would-be attackers although this has not always saved them from destruction. In the 10th Century, the Jewish queen ‘Judith’ tried to eradicate Christianity by burning many of the churches and their valuable Christian works. An invasion led by Ahmed ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi ‘the Conqueror’, a Somali General in the 16th Century, also destroyed many treasures and signs of the destruction can still be seen in many of the churches today. The Gheralta Mountain chain, deep within the northern high plateaux of the Tigray region, is highly picturesque, and I sat on a high rock hill in the garden of a lodge taking in the big-sky view of a sunset over the cartoon cardboard cut out shapes of the mountain silhouettes. It was market day and the huge plain in front of me thronged with people and their newly acquired livestock, walking back to their homes. The following morning a hired minivan dropped us off outside St. Gabriel’s church, a beautiful freestanding structure with whitewashed walls holding three equidistant domed windows on each side.

A green slanted roof leads up to a second section of squat roofing with a stubby tower a meter or so high, painted blue with two tiny red windows. On top of this and to either side, three bulbous metal rods hold beautifully ornate symmetrical crosses. The middle and highest of the three is as if two crosses have been slotted together at right angles, so that you can see the symbol from any direction. This and many of the other church buildings, which are often similar in design, always seem to remind me of Tibetan architecture. I have occasionally heard Ethiopia referred to as ‘The Tibet of Africa’, which I do not think an outlandish statement. Intrepid Irish explorer and travel writer Dervla Murphy notes in the prologue of her wonderful account of In Ethiopia with a Mule, first published in 1968, that: “There is a certain similarity between the developments of Ethiopian Christianity and Tibetan Buddhism. In both cases, when alien religions were brought to isolated countries the new teachings soon became diluted with ancient animist superstitions; and so these cuttings from two great world religions grew on their high plateaux into exotic plants, hardly recognizable as offshoots of their parent faiths.”

Talking with local Ethiopians

I had hired a boy called Bennie as a guide and translator and we both said goodbye to the driver and also a cheerful policeman who had come along for the ride. We had shared a joke during the trip as I had complimented the policeman on his beautifully patterned green and red silky shamma, which he wore loosely in a loop around his neck. He had accepted the compliment, saying that it was of the very best quality made by the Afar people in the east. This was met with enthusiastic confirmation by both the driver and Bennie, who explained that it cost upwards of 800 Birr [40 Dollars US]; an impressive sum. The policeman unwrapped it from his neck and splayed the material out lovingly for me to inspect. There was a round sticker in one of the corners that we all read at the same time – ‘Made in China’. We all fell about laughing as the minivan bumped along the sandy track, although I chose not to delve into the more negative connotations of this microcosm of the modern world. Bennie’s smile creased the twin scars on either side of his eyes, a common sign of Christianity here, as well as a small cross either scarred or tattooed in the middle of the forehead.

Our trek began with a scramble up a terraced mountainside with occasional stretches of winding pathway to unglamorously gain some height. Once on the top the views were instantaneously fantastic. We trotted along the ridge of sloping laval rock, alternatively looking down to the acacia-dotted plain to our right, or to majestic sepia paint stoke lines of rolling foothills on our left. After a small descent we came around a smooth bend in the track over bright purple rock. I remember thinking I had never seen a bright purple rock before. We ascended up to our first rock church through the gateway of the priests’ dwelling, a large dry stone construction of sandy red rock; the rectangular stones placed together as well as you could hope to see anywhere. The Tigrayans, in their arid, rocky plateaux, mainly live in dry stone buildings compared with much of the rest of the country whom, in their lusher pasturelands, use wood and dung to construct their homes.

Experiencing a church service in Ethiopia

I stepped through the roofed archway of the outer wall, a large iron bell hanging from a sturdy beam. Three snotty nosed ten year-olds were loitering in the entranceway and flashed insecure smiles at me. Some women were sitting in the shade of an acacia tree. I dropped my pack and carried on through a gap in a stone wall along a thin path leading around to a cliffside. As I rounded the corner I came across six women and an elderly priest standing at the entrance to a doorway cut into the cliff, framed with wooden beams and a thick door hanging open with the sound of chanting and prayers emanating from the gloomy inside. This was the rock-hewn church of Yohannis Maqudi. The women all wore cream shammas and had beautifully braided hair; thin and tightly woven in different angular patterns down on the front section of their heads, their long wavy afro curls then either flying out at the back in large waves or in continuing carefully arranged linear folds and designs. Often they wear a single large silver-coloured earring high up on their left ear that hangs in an upturned crescent.

One of the women gestured to me to take off my boots. I did so and went and sat in a small hollowed out cave next to the priest. Everyone had bare feet. The priest wore a cream turban and held his horsehair fly-whip in a relaxed manor, the symbol of his vocation. His feet were so black that they had started to become different colours within the blackness. I remember thinking that that is what the black of a black hole in space must look like. I was strangely fascinated by them. He had a kind face and sang in a soft melodious voice. At one point everyone got down on their knees and elbows on the sandy ground to pray and I did the same and it felt good. After some sign language it was conveyed to me that I could enter the church if I paid the now regulated donation and I did so. I was led into a second cave entrance on the left which led through a dark curving passage, a rudimentary cross chiseled onto the ceiling. This in turn led into the main church up over a second rock-hewn doorway bolstered with thick wooden beams. Inside there were many women and men, all dressed in cream shammas. A priest was intoning prayers while another held a very large latticed brass cross.

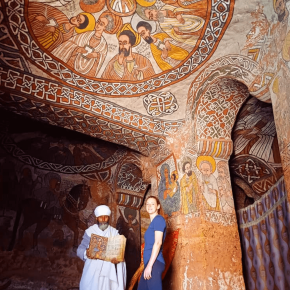

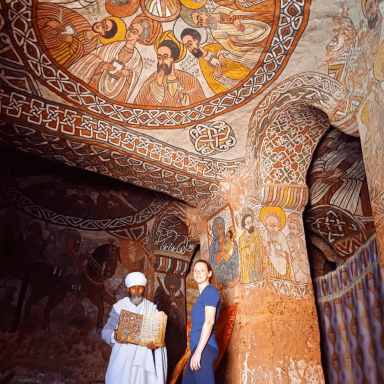

The frescos of the rock churches

The frescos, painted onto the hand-chiseled walls, were from another time, another world: men with swords were arranged in a row of horses ready for battle. Two demons had got hold of a man and while one held him upside down by his feet the other poked him in the eye with a spear. Warrior saints, the twelve apostles, and Fasilides, Emperor of Ethiopia 1632 – 1667, were all speaking to me through speech bubbles written in Ge’ez, the ancient language of the Ethiopian Christian Church. Their eyes all flashed menacingly. The priests continued to chant with the congregation occasionally murmuring replies in response. After the mass the women all filed out through the door I had entered by and sat outside under the shade of the acacia. The men all left by the other door and walked to the priest’s quarters where they and I sat on earthen benches around a sunken floor. We drank talla, the millet-based beer, and ate the spongy injera with a chili sauce as everyone was fasting for Genna, the Ethiopian Christmas taking place in a week or so. The all-male atmosphere, though jarring strongly with my Western associations of a Christian community activity, was extremely welcoming and hospitable; the priests showing a genuine curiosity in me and making sure I wanted for nothing.

The children silently served their elders with marked deference. The size of my pack was the main topic of conversation, with the priests joking that only a donkey would carry a load like that. After the hearty meal and numerous cups of talla later, we shouldered our packs and left the compound. One priest followed us out, loudly demonstrating that I should give him money because he had used the keys to open the church, the protestations of whom I serenely ignored. There is a strange contradiction in many of the people here, and indeed the whole country, which I had been unable to consciously articulate until coming across another insightful passage of Dervla Murphy’s: “… one of the strangest paradoxes of highland life is the extraordinary assurance and dignity – of a particular quality not found at all levels in European societies – which distinguishes so many of the peasants. Even in such a remote region as this, and when confronted with such a disquieting phenomenon as myself, their innate courtesy rarely fails them. Yet in many ways they are ignorant, treacherous and cruel to a degree – which has led some foreigners to dismiss their more attractive aspect as a form of deceit, or at best a meaningless routine of etiquette. But to me the two aspects, however contradictory, seem equally genuine.”

Staying with an Ethiopian family in a beautiful valley

We came down through a lush eucalyptus grove, over a dry sandy riverbed then up the other side on a path cleft through steep earthy orange embankments. A small freestanding church was nestled into the side of the cliff up on our right hand side. Its tin roof and cross on top painted in pleasing bright colours. A bird darted across the valley with oily black feathers and bright auburn wing tips. As we came to the top of a small hill, the dry stone wall-lined fields of an idyllic valley opened out before us. Young girls playing next to a huge pile of teff were screaming their heads off as I slowly walked down the track “faranji! [foreigner!] hello! farangi! hello! farangi…” as a never-ending welcome. The valley was a patchwork of perfectly leveled fields dotted with acacia, olive and eucalyptus. Cacti ran in thick groves, used as a natural fencing around the properties. A peach sunset warmed the sky in the west with rays of gold slanting down beneath fluffy cumulonimbus in shafts onto the valley floor. To the east, Mariam Bagulisha, a gently domed pinnacle of rock, sored up from the flat ground into a dreamy sky, cartoon-like in the half-light. I felt too ethereal to be real.

I felt that whatever I had been hoping to find in this country, this was it. I mean, this was really it. I sat down with my laptop (I had rather stupidly brought it along for the trek) on my knees to jot down some notes and six children crowded around me. One of the older boys could read English and spoke out the words as I typed them. They asked to see pictures and as none of them had been to Lalibela I showed them some videos of the churches there. A woman of approximately seventy greeted us and welcomed us into her house. Although we had a tent and there is a beautiful camp spot in the valley by an olive grove and water pump, we decided to accept her hospitality and stay the night. We ate injera and a delicious savory pancake with the shiro bean curd, sipping scolding sweet buna in the torchlight of a large whitewashed room. We washed our hands and feet afterwards outside in the courtyard next to a tethered cow. A small acacia sapling was protected from the livestock by oversized wooden fencing to one day grow strong and provide shade for the earthen-floored compound. It was New Year’s Eve. I was asleep by nine o’clock on a small earthen platform raised off from the floor of the room.

Climbing to the largest church in the Gheralta Mountains

In the morning we set off through the patchwork valley to tackle the steep ascent to the church of Abuna Abraham, the largest in the Gheralta Mountains. Located at the top of a sheer cliff, the church overlooks a long stretch of plain far below. Its interior is nothing short of magnificent; eleven huge pillars of living rock souring up to the vaulted ceiling covered in colourful 7th Century frescos showing the deeds of Abuna Abraham himself. Bennie gave me a rundown of the images: “Once upon a time there was no water and the people were thirsty so the saint placed pots of water on a lion’s back to bring to the Christians,” as he pointed to the painting of the beast above the doorway. “And here, once when he was walking from Amhara to Tigray, a large lake prevented him and his followers from completing the journey, so he placed the cross at the end of his staff into the water like Moses and the waters parted and they were able to cross.” In the fresco depiction his eyes are shining white with a holy light as his staff touches a rectangular box of water with fish painted at odd angles over the stone. Another depiction shows the saint holding a large young male lion so its smaller brother can suckle his mother.

The priest, holding his wooden prayer stick and a metal rattle did a little prayer dance, murmuring intonations. Bennie translated: “God, I ask from you from my heart that you give me good health and peace.” Upon descending we fell in with two monks and several teenagers walking through a dry riverbed. We walked up through a small rift as two mountains peeled away on either side of us. On the right hand side of the path, across a dry pebbly river floor, a troop of gelada baboons lounged about on flat shale. We all rested at the top in the hot sun. One of the boys insisted on carrying my pack to demonstrate Ethiopian hospitality to travellers and to show off to his friends. Dutifully carrying it down into the village he didn’t allow the strain to show, although it is the only time I recall seeing a Habasha [an Ethiopian from the northerly region of old Abyssinia] sweat. After a sneaky glass of talla at the local inn we walked along the plain which opened out into grassland; acacia and sycamore trees so delicately placed so that it looked like a Hollywood ‘African’ film set, huge stalagmites of rock creating a cowboy backdrop.

Staying with a young Ethiopian singing family

We lounged under the largest sycamore tree, its incredible branches reaching out over fifteen meters from its huge twisting trunk. Birds of all kinds, colours and calls, had flocked to this marvel and it was a delicious feeling to lie in the long grass eating peanut butter sandwiches and listen to their chatter. This would have been an ideal campsite but it was still only mid-afternoon and Bennie and I fancied some company again so we eventually loaded our packs and continued on. That night I stayed at the house of Haile, a member of the guiding association in the Gheralta. He was not home when we arrived but his wife, Gabriel, took great care of me alongside her seven children, even though my arrival had not been pre-arranged. An impromptu English lesson began with her daughter Terhaus, an incredibly bright ten-year-old girl in the 4th grade, and her son Hamben, a twelve-year-old in the grade above. They would scribble down words in English that I gave them: ‘House’. ‘Cow’. ‘Mother’. ‘Light’. I corrected the spelling and then they would write the words again on the back of the paper to prove they weren’t cheating, although they often did, inviting squeals of remorse when I tickled them as punishment.

Their cozy home is made up of two main buildings surrounded by a dry stone wall, creating the earthen-floored compound common in most homesteads of the region. The main longhouse was very large with a large number of sheep pelts laying on the perimeter seating around the walls or hanging from two tree trunk pillars. Two flat raised areas at the eastern end served for beds. The walls were whitewashed with a auburn strip running from the ground about a meter up. Decorative items hung from the walls; a single-stringed masinko instrument, skin gourds and colourful weaved injera stands. One item of luxury was a large gas lamp suspended from the ceiling, its tubing linked to a canister outside through the wall. This emanated a soft pleasant light over our classroom. After we had eaten all the children gathered around my bed. Hamben took down the masinko and played while the others clapped, led by their mother Gabriel. Terhaus did a little dance in the middle, wriggling her shoulders and stomping her feet. It was like a rendition from the Ethiopian version of the Vonn Trapp family, and I have to say my heart melted a little bit in my chest.

In the morning Gabriel cooked me some eggs then made buna, carefully roasting the coffee beans and waving the smoke over my head as a blessing. She struck me as a happy woman despite the no-doubt exhausting work of raising seven children. Bennie came down from his house which wasn’t far away, and we set off, the path leading us west through a valley between the cowboy mountains. We walked through some deep sand before coming to a green rush-filled stream where women were washing clothes and filling their yellow water containers. The path wound up the steep mountain above us where workers were in the process of building a large set of stone stairs leading up to a small church, perched halfway up the mountainside. They loaded the stone into metal containers draped over the backs of donkeys, and helped to push the poor beasts up the already completed stairs, unloading them at the top. I walked up past them saying hello, gave a little jump up onto the earthen path at the top and carried on up the steep incline, beads of sweat rolling off my forehead in the hot sun.

A work party refurbishing a church

I reached the entranceway to the freestanding church, a sandy path leading up from a stone-roofed gate to where about forty men and women were milling about or sitting in the shade of the eaves of the roof. Similar in design to St. Gabriel’s, it had hundreds tin tassels suspended from the eaves, making a pleasant tinkling sound in the breeze. The men of the group turned out to be a work party and showed me the inside, which was filled with mounds of shoulder-high sand. I came back out to find Bennie looking peaked after a conversation with the workers who said that they wanted to charge me 200 Birr [ten Dollars US] to enter and film in the church. I got them down to 50 Birr and went back in with my camera blinking red in the half-light. I was surprised and excited to find that the freestanding church actually led back into a massive rock-hewn hall cut into the mountainside, its many pillars curving up and out at the top into an exquisitely carved chequered stone-cut pattern on the ceiling. Their frescos of the pillars had fallen away to time and disrepair and there was much erosion of the stone. It was here that the men were working. It was a very authentic experience to be in one of these marvels with many bodies milling about around me, the chink chink of chisels striking the stone floor.

The men were laying concrete to level the uneven stone floor, which seemed to me a gross error, albeit a practical one as they wanted to use the space for worship. I almost walked into a freshly laid section and was shooed away with laughter. I stepped past several men chiseling stone steps into a small ante-room, carved deeper into the mountainside. I later heard myself on the video recording saying “very good” in a strange voice. It was a little creepy in there. All eyes were on me and I suddenly felt claustrophobic and made a beeline for the cave exit. I stopped in the doorway and turned back saying “Amisiginalo [thank you], salaam, ciao” like some sort of awkward celebrity, before stepping into the sunlight. The man I had given the 50 Birr to offered his services as a guide up and over the mountain, the highest in Gheralta, into the next valley, which was fortunate as Bennie was unsure of the route. I have forgotten his name now but he was a humorous ex-soldier with a cheeky grin, and wore an old camouflage jacket.

The view from the highest mountain

He made the mistake at the outlet of telling Bennie a ‘funny’ story of how, to his mind, he had grossly overcharged some tourists for a few hours’ work by taking them up to see a single church in the area. His smile faded somewhat as Bennie translated and I slowly nodded my head instead of laughing, realizing he had metaphorically shot himself in the foot in the hopes of over-payment for this day’s excursion. We set off up the mountain and the walk just got better and better. Soon we were well above the church, looking down to see it nestled in the side of the conical valley. Then we were up and out of it, striding past gigantic red faces of sandstone cliffs that led down into a deep river valley, a silvery snake of water in wide looping chicanes meandering off into the distance. We ascended up to the plateaued summit of the Mount Kemmer, the highest mountain in the region, standing a straight rectangular tabletop above his jumbled and unruly younger brothers; their peaks and curved promenades jostling and fighting for prominence below him.

I was reminded of the comment of one of the British soldiers under General Napier’s 1867-8 campaign against the Emperor Tewodros II: “They tell us this is a table land. If it is, they have turned the table upside down and we are scrambling up and down the legs.” It certainly felt like that as I slogged up in the midday sun, although the 360° view afforded from the top would have made it worthwhile twice over. This British expedition into Abyssinia was a rather unique affair. Upon capturing some British subjects in order to gain the attention of and force concessions from Queen Victoria, Tewodros II, also known as Theodore, overplayed his hand by continually refusing to release them, piquing the pride of the British Empire that was then at its height. At the staggering cost of nine million pounds sterling at the time, Napier successfully led an expedition into the interior from the Red Sea, resulting in the successful rescue of the prisoners and the death of Theodore by his own hand; using the very silver-engraved pistol Queen Victoria had given him as an earlier gift. During his reign he did much to unite and improve the country and is still remembered as a hero by many, his golden statue taking pride of place in the center of the castle city of Gonder.

A flashback to Richmond Upon Thames, London

This recollection in turn reminded me of the moment I had first decided to visit Ethiopia, whilst sitting at my desk in my Richmond apartment in West London. The lead-grated windows glowed in the soft light of a fading crimson autumn evening as I scoured my book-lined windowsills to see if I had anything relevant on the country. The only thing I could dig-out was George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman on the March, which places the insufferable Flashman as the fictional protagonist in the historical setting of Napier’s expedition. I began to read it immediately, then I ran a bath and carried on reading for the rest of the evening. In a rare moment of non-self-serving patriotism, Flashy comments that the campaign itself was; “…just a decent resolve to do a government’s first duty: to protect its people, whatever the cost.” I gave a salute to no one in the bath. As expected, it was the usual sexist, racist and politically incorrect account of the misadventures of the lecherous and cowardly swashbuckler one comes to expect from all the Flashman Papers. Although I learned absolutely nothing about the country from the account, it certainly gave me a chuckle or two and whet my appetite for a spot of adventure. I resolved to buy some proper books on the subject.

But I digress: we came down out of the sun and sat in the shade of an acacia growing next to a tiny hermitage, chiseled out from a domed anthill-like summit of stone. We ate small dry cakes and vacuum-packed dates imported from Saudi Arabia. I opened the pack with a seven-inch Austrian army-issue Glock knife that I had on loan for this trip, its primary employment having been the spreading of peanut butter over sandwiches. Our scout’s eyes flew to the object and he gave me an appreciative nod. I had noticed a fascination with the knife by nearly all of the locals who had seen it, many demanding to handle and play with it: for their rural way of life a tool of such practicality and workmanship being a prized possession. A thin walkway has been chiseled out around the side of the anthill, leading to a small locked metal doorway. A small circle in the exterior wall of stone acted as a window and through this I looked down to see the stomach-churning drop below, curving down and out to stalagmite spines of sandstone pillars jutting out from the desert like a dinosaur’s tail.

Staying in a local village and listening to stories

Although easily exceeding a 50-storey building in height, from our position these pillars looked tiny in the heat-haze. Encased in the tallest of these pillars, about halfway up, is the most ostentatious of all the rock-hewn churches; Abu Yemata, whose name I kept forgetting, calling it Akuna Matata instead to annoy Bennie. To my right, a tiny hermit’s cave had been cut into a sheer face of the table mountain. I couldn’t help wondering who had chosen to live in there, and what, if any, revelations it had afforded them. After a long walk we eventually came down into a plain of farmland, parting with our guide and greeting a young boy goat-herding with his father. We reached the small village of Agoza, which means ‘the skin of a sheep’ and refilled our water bottles at a water pump surrounded by cacti and thorns on the edge of a dry sandy riverbed. What looked like the entire village’s adolescent community had congregated here and we washed the salt off our faces, necks and arms, joking around with the kids.

We walked across stony fields of red soil to the house of some of Bennie’s wife’s relations, where two sisters Yeshi, 17, and Abrihat, 19, live. They are both very pretty and we enjoyed sitting with them drinking talla beer then buna from freshly roasted coffee beans, eating our injera with the ever-present shiro bean curd. Their house was beautifully built with a twisted olive trunk as the main supporting pillar. Upon asking, I was told that their father had passed away around the time when Yeshi was born and their mother, a strong looking woman called Nigisti, had raised them herself. I asked Yeshi if she wanted to go to college and she said she had been working for a Chinese contractor building roads for a month to save money for this before he had skipped town without paying her or any of the other workers. College starts in February and it will now be very difficult for her to attend. Abrihat had a two-year-old daughter but was not married and there was no sign of the father. These trials and tribulations did not seem to be discussed as if being out of the ordinary. Yeshi wore a blue dress and had her hair tied backwards in braids over her head in a pretty pattern, her sister a loose and baggy T-shirt.

With Bennie translating, I told them about what we had seen that day and asked Yeshi if she had explored many of the mountains. Her reply was; “How can we do that, without a faranji to take us there?” It was clear that both sisters and their mother all wanted to move into a large town or city but were restricted by poverty. Abrihat slept with her daughter in the earthen platform next to mine, keeping watch over her all night with a solar light. A steep climb led us out of the village the next morning, the path taking us up through cactus groves perched on the side of sheer red cliff faces, eagles gliding above us on the thermals. It was yet another completely new environment within the mountain chain and I couldn’t help gasping at the wonder of the place. We came around the last of these cliffs to an open spot and stopped for lunch with a shepherd wearing an enormous cream turban like a snake charmer. We were at the northernmost edge of the chain now and I could see for miles across the desert plain to waves and waves of mountains in the distance, including the holy mountain of Axum, crashing upwards on the horizon in sharp grey bursts.

Continuing our journey to St. Michael’s Church

We eventually descended to the church of Abuna Gabre Mickail Koraro, or, St. Michael’s, Bennie having previously called ahead to the priest on his cellphone to come and unlock it for us. A relatively younger church, it was founded in the 17th Century by King Gabre Mesker. Nestled in the side of a sheer mountain cliff of light grey stone, parts of the exterior around its windows are been painted in a dark crimson. Tibetan images of Lhasa again flashed into my mind. We entered and the frescos were the most impressive of all the churches I saw in the region. With a blue and yellow theme, they leap out from the high vaulted ceilings and twelve delicate pillars in a cacophony of martyred saints: St. Peter is having his head cut off, St. Jacob is being stoned, his body filling up with large rocks, St. Paul is being skewered with numerous spears, another saint is hung upside-down, another is killed with dogs. All of them have their tongues poking out. The 12th Century hermit-saint Tekle-Haimanot is also depicted who, in the manner of an anchorite of the early church, stood on one leg in meditation for seven years until the other withered and fell away.

Despite the rather gruesome subject matter, it is a calming place to sit in the cool away from the hot sun and the three of us sat in the middle of the cavern alone for quite some. We eventually headed down the mountain through a deep split in the rock, five stories high and just wide enough for two men to descend abreast. We came across a beautiful camp spot in the lee of a huge natural cave in the mountainside next to a natural spring bubbling close to some small fort-like dry-stone ruins. I pitched our tent and we had a simple dinner. A small dirt track led from the cave down to an acacia-dotted plain smoldering the dying sunlight. In the morning we were collected by our minivan and driven around to the base of the dinosaur’s tail we had seen from the summit two days previously. From the ground looking upwards it was a completely different experience and didn’t look a like a dinosaur’s tail at all; more like a block of NYC high-rises in stone.

Visiting the famous Abuna Yemata Church

I practically skipped up the short ascent to the base of pillars. The ascent then became very steep to the point where I was climbing with ropes and a provided harness over a particularly tricky section. Upon reaching the top of a massive boulder, wedged about halfway up between the two largest stone towers, I met a small group of Spanish tourists. I chatted with their tour leader for a while, both of us equally rejoicing in the beauty of the mountains and bemoaning our fear of vertical heights. From the top of the wedged boulder we could see that windows of Abuna Yemata Atan Guh (“Akuna Matata?”) had been cut into the side of the largest pillar. To get inside we had to shuffle along a meter-wide ledge with a sheer unprotected vertical drop on the left that goes down may hundreds of meters, although I’m not exactly sure of how many as I didn’t look. Then you duck inside a small round hole and again you are awarded with the cool, damp, mind-blowing interior of a place that shouldn’t exist.

During the late 5th Century, nine saints travelled as missionaries to Axum and were influential in the growth of Christianity in the region. Although legend has them all as Syrian in origin, many have been traced back to Constantinople, Anatolia and even Rome. Welcomed by King Ella Amida in Axum in the north, the son of the first Christian kings, the nine ‘Syrian’ saints then made their separate ways into the country, founding different churches and monasteries as they went. One of the nine, Saint Yemata Atan, came to Gheralta and legend has it that he rode his horse up the sheer wall to carve the church now named after him; his horse’s hoofmarks still imprinted and visible in the stone. For those unable or unwilling to make the climb there is the equally impressive option to visit the church of Abuna Mariyam Koko, which is a short drive from Abuna Yemata. The climb is more regular although I chose to do this particular ascent in the dark at four o’clock in the morning. The reason being that it was Genna [Ethiopian Christmas], and I wanted to see the holy mass that is performed throughout the night for the occasion.

Viewing the festival of Genna throughout the night

After making the ascent to the church by torchlight, we were greeted by ten priests who were standing in the middle of the beautifully carved church. One of them was beating a huge leather drum covered with cowhide, held in place by a thick leather strap over his shoulder. He had a pointy beard like a Spanish Conquistador and did a little dance as he beat both ends loudly and rhythmically. The other priests stood around him in a circle singing and shaking their metal rattles in time. Waves of incense filed the air. The music was hypnotic and through a microphone was played out from a round speaker wedged in a small hermitage window cut into the side of the mountain, the wailing prayers drifting down the 400m cliff face to the houses and farmsteads below. The service lasted all night, the priests taking turns to do readings or recite prayers, while others sat or snoozed on the wooden benches. One priest had given up completely and, fully wrapping himself in his shamma so that he looked like a leper, sat sleeping with his back against a large stone-carved pillar, his head between his knees.

I went outside at first light to watch the sunrise over the mountain chain next to the tannoy speaker, a priest in turn wailing like a Muezzin then praying very low and fast. The ledge I was standing on fell away in a perfectly vertical drop to the flat Tigrinyan farmsteads on the tableland below, on my right the Gheralta chain rising to attention like soldiers on morning parade. Before the sun rose over the horizon it ignited a small line of fluffy clouds directly in front of me in a searing coral through to gold, so bright I couldn’t believe my eyes could take in a colour like that without burning. It was very cold. I waited for the sun to come up with my teeth chattering and the wail from the tannoy reverberating in my ears.